What is a Winging of Scapula?

Winging of the scapula, also known as scapular winging, is a condition in which the medial or lateral border of the scapula (shoulder blade) protrudes away from the back, causing a noticeable deformity or "wing-like" appearance. This can occur as a result of weakness or paralysis of the muscles that stabilize the scapula against the rib cage, such as the serratus anterior muscle or the rhomboid muscles.

The condition can be caused by a variety of factors, including nerve damage, muscle weakness or atrophy, trauma, or underlying medical conditions such as muscular dystrophy or thoracic outlet syndrome. Symptoms of scapular winging may include pain or discomfort in the shoulder, neck or back, difficulty raising the arm or performing overhead activities, or visible protrusion of the scapula.

Treatment for scapular winging typically involves addressing the underlying cause, such as physical therapy to strengthen the affected muscles or surgery to repair nerve damage or correct skeletal abnormalities. In some cases, assistive devices such as braces or slings may also be recommended to help support the affected arm and shoulder.

Related Anatomy

The scapula, also known as the shoulder blade, is a flat, triangular bone located on the back of the thorax (chest). It is connected to the clavicle (collarbone) and the humerus (upper arm bone) by muscles and ligaments, and it articulates with the rib cage at the acromioclavicular joint.

The scapula has several bony landmarks, including the spine, acromion process, coracoid process, and glenoid cavity. The spine is a ridge of bone that runs diagonally across the posterior surface of the scapula, separating it into two unequal portions. The acromion process is a bony projection that extends from the top of the scapula and forms the tip of the shoulder. The coracoid process is a smaller bony projection that extends from the front of the scapula, just below the clavicle. The glenoid cavity is a shallow depression located on the lateral aspect of the scapula, and it forms the socket of the shoulder joint.

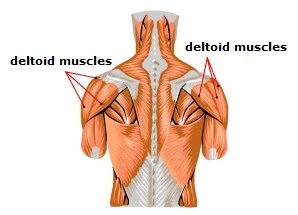

The muscles that attach to the scapula are responsible for stabilizing and moving the shoulder joint. These include the rotator cuff muscles (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis), as well as larger muscles such as the deltoid, trapezius, serratus anterior, and rhomboids. The serratus anterior muscle, in particular, is important for stabilizing the scapula against the rib cage and preventing scapular winging. It arises from the upper eight or nine ribs and attaches to the medial border of the scapula, and it is innervated by the long thoracic nerve.

Causes of Winging of Scapula

Winging of the scapula can be caused by a variety of factors, including:

Nerve damage: Damage to the nerves that supply the muscles responsible for stabilizing the scapula can result in scapular winging. The most common nerve involved is the long thoracic nerve, which supplies the serratus anterior muscle. Other nerves that can be affected include the spinal accessory nerve and the thoracodorsal nerve.

Muscle weakness or atrophy: Weakness or atrophy of the muscles that stabilize the scapula against the rib cage, such as the serratus anterior or the rhomboid muscles, can also cause scapular winging. This can be due to a variety of factors, including disuse, nerve damage, or muscle disorders such as muscular dystrophy.

Trauma: Direct trauma to the scapula or the surrounding area can cause damage to the muscles or nerves that control scapular movement, resulting in scapular winging.

Underlying medical conditions: Certain medical conditions such as thoracic outlet syndrome, myopathies, or neuropathies can lead to scapular winging.

Surgery: Surgery involving the shoulder or the chest wall can sometimes result in scapular winging as a complication.

It's important to identify the underlying cause of scapular winging in order to determine the most appropriate treatment approach.

Symptoms of Winging of Scapula

Symptoms of winging of the scapula can vary depending on the underlying cause, but may include:

Visible protrusion of the scapula: The medial or lateral border of the scapula may protrude away from the back, giving a noticeable deformity or "wing-like" appearance.

Pain or discomfort: Patients may experience pain or discomfort in the shoulder, neck, or upper back, particularly when using the affected arm or performing overhead activities.

Weakness: Weakness or difficulty with arm elevation or pushing tasks may be present, as the muscles responsible for stabilizing the scapula may be compromised.

Limited range of motion: Patients may have limited range of motion in the shoulder joint, particularly when trying to lift the arm above shoulder height or behind the back.

Muscle atrophy: Over time, the muscles responsible for stabilizing the scapula may become smaller or weaker, resulting in muscle atrophy.

It's important to seek medical attention if you experience any of these symptoms, as early diagnosis and treatment can help prevent complications and improve outcomes.

Differential Diagnosis

Winging of the scapula is a relatively rare condition, and there are several conditions that may present with similar symptoms. Differential diagnosis for scapular winging may include:

Rotator cuff injury: Injury or tears to the rotator cuff muscles can cause pain, weakness, and limited range of motion in the shoulder, which may mimic the symptoms of scapular winging.

Shoulder impingement syndrome: This condition occurs when the tendons or bursae in the shoulder become compressed or irritated, resulting in pain and limited range of motion. Shoulder impingement can also cause weakness in the affected arm, which may be mistaken for scapular winging.

Thoracic outlet syndrome: This condition occurs when the nerves or blood vessels that pass through the thoracic outlet become compressed or pinched, resulting in pain, weakness, and numbness in the arm and hand. In some cases, thoracic outlet syndrome may also cause scapular winging.

Cervical radiculopathy: This condition occurs when a nerve root in the cervical spine becomes compressed or irritated, resulting in pain, weakness, and numbness in the shoulder, arm, and hand. Cervical radiculopathy can sometimes be mistaken for scapular winging.

Muscular dystrophy: Muscular dystrophy is a group of inherited disorders that cause progressive muscle weakness and wasting, which can result in scapular winging in some cases.

Trauma or injury: Trauma or injury to the shoulder or back can cause pain, weakness, and limited range of motion, which may mimic the symptoms of scapular winging.

It's important to consult with a healthcare professional if you are experiencing any symptoms of scapular winging or if you have any concerns about your shoulder or back health. A proper diagnosis is crucial for effective treatment and management of your symptoms.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of scapular winging typically involves a thorough physical examination and a review of the patient's medical history. The healthcare provider may ask the patient about the onset and duration of symptoms, any history of injury or trauma, and any underlying medical conditions that may contribute to the symptoms.

During the physical examination, the healthcare provider will assess the patient's range of motion, muscle strength, and the appearance of the scapula. They may ask the patient to perform specific movements or exercises to evaluate the function of the muscles responsible for scapular stability. The healthcare provider may also palpate the scapula and surrounding muscles to identify any areas of tenderness or weakness.

Diagnostic imaging, such as X-rays, MRI, or CT scans, may also be ordered to evaluate the bones, joints, and soft tissues in the affected area. Electromyography (EMG) may also be used to assess nerve and muscle function.

If scapular winging is suspected, the healthcare provider may perform additional tests to identify the underlying cause. This may include blood tests, nerve conduction studies, or a biopsy of the affected muscles.

The diagnosis of scapular winging can be complex, and it's important to consult with a healthcare provider who specializes in the evaluation and treatment of shoulder and back conditions. A proper diagnosis is crucial for developing an effective treatment plan and improving outcomes.

Treatment of Winging of Scapula

The treatment of scapular winging depends on the underlying cause and the severity of the symptoms. In some cases, conservative management may be sufficient, while in other cases, surgery may be necessary. Some common treatment options for scapular winging include:

Physical therapy: Physical therapy can help improve range of motion, strengthen the muscles responsible for scapular stability, and improve overall shoulder function. Your physical therapist may recommend specific exercises and stretches to target the affected muscles and improve your symptoms.

Bracing: A scapular brace can help support the shoulder and improve scapular stability. Depending on the severity of the scapular winging, the healthcare provider may recommend an off-the-shelf or custom-made brace.

Medications: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may be recommended to help manage pain and inflammation associated with scapular winging.

Injections: Corticosteroid injections may be recommended to reduce inflammation and pain in the affected area.

Surgery: In severe cases of scapular winging, surgery may be necessary to correct the underlying cause of the condition. The surgical approach will depend on the cause of the scapular winging, and may involve repositioning or reattaching the affected muscles, removing any abnormalities in the bone, or repairing any damage to the nerves or blood vessels in the area.

It's important to consult with a healthcare provider to determine the most appropriate treatment plan for your specific case of scapular winging. With proper treatment and management, most patients with scapular winging can experience significant improvement in their symptoms and function.

Physiotherapy Treatment in Winging of Scapula

Physical therapy is an important component of the treatment plan for scapular winging. A physical therapist can help improve scapular stability and shoulder function through specific exercises and manual techniques. The goals of physical therapy for scapular winging may include:

Improving scapular stability: The physical therapist may recommend exercises to strengthen the muscles responsible for scapular stability, such as the serratus anterior, trapezius, and rhomboids. Strengthening these muscles can help improve the position and function of the scapula, which can improve shoulder function and reduce symptoms.

Improving range of motion: The physical therapist may recommend stretches and exercises to improve range of motion in the shoulder and upper back. This can help improve overall shoulder function and reduce pain and stiffness.

Correcting postural abnormalities: The physical therapist may assess the patient's posture and recommend exercises and techniques to correct any postural abnormalities that may be contributing to the scapular winging.

Pain management: The physical therapist may use manual techniques, such as massage or mobilization, to help reduce pain and improve tissue mobility in the affected area.

Education: The physical therapist can educate the patient on proper body mechanics and techniques for performing daily activities to help prevent further injury or aggravation of the condition.

The specific treatment plan will depend on the underlying cause of the scapular winging and the severity of the symptoms. The physical therapist will work with the patient to develop an individualized treatment plan based on their specific needs and goals.

Exercise for Winging of Scapula

Exercises that focus on strengthening the serratus anterior, trapezius, and rhomboid muscles can be beneficial for improving scapular stability and reducing symptoms of scapular winging. Here are some exercises that may be recommended by a physical therapist or healthcare provider:

Wall slides: Stand with your back against a wall, with your feet shoulder-width apart. Place your hands on the wall at shoulder height, with your elbows bent to 90 degrees. Slowly slide your arms up the wall, keeping your elbows and wrists in contact with the wall. Hold for a few seconds, then slowly lower your arms back down. Repeat for 10-15 repetitions.

Scapular push-ups: Start in a plank position, with your arms straight and your shoulders directly over your wrists. Slowly lower your body towards the ground, while simultaneously squeezing your shoulder blades together. Push back up to the starting position, while maintaining the squeeze in your shoulder blades. Repeat for 10-15 repetitions.

Prone Y-T-W-L: Lie face down on a mat or bench, with your arms hanging down towards the floor. Lift your arms up and out to the side to form a Y shape, then lower back down. Lift your arms up and out to the side to form a T shape, then lower back down. Lift your arms up and out to the side to form a W shape, then lower back down. Finally, lift your arms up and out to the side to form an L shape, then lower back down. Repeat for 10-15 repetitions of each position.

Resistance band rows: Attach a resistance band to a stable object, such as a door or pole. Stand facing the object, with the resistance band in both hands. Bend your knees slightly and lean forward from the hips, keeping your back straight. Pull the resistance band towards your chest, squeezing your shoulder blades together. Slowly release back to the starting position. Repeat for 10-15 repetitions.

It's important to work with a healthcare provider or physical therapist to determine the most appropriate exercises for your specific case of scapular winging. They can help develop an individualized exercise plan based on your specific needs and goals.

Complications

In some cases, untreated or improperly managed scapular winging can lead to complications, such as:

Shoulder instability: Scapular winging can lead to instability of the shoulder joint, which can increase the risk of dislocation or subluxation (partial dislocation) of the shoulder.

Rotator cuff injuries: Scapular winging can also increase the risk of rotator cuff injuries, as the muscles that stabilize the scapula and the rotator cuff muscles work together to support shoulder movement.

Chronic pain: Scapular winging can cause chronic pain in the shoulder, neck, and upper back, which can affect daily activities and quality of life.

Decreased range of motion: If scapular winging is left untreated, it can lead to a decreased range of motion in the shoulder joint, which can limit the ability to perform daily activities and participate in sports or other physical activities.

Muscle atrophy: Chronic scapular winging can also lead to muscle atrophy (wasting) in the affected muscles, which can further weaken the shoulder and limit function.

It's important to seek prompt medical attention if you experience symptoms of scapular winging, such as shoulder pain, weakness, or a protruding shoulder blade. Early diagnosis and proper management can help prevent complications and improve outcomes.

How to Prevent Winging of Scapula?

Scapular winging can be prevented or minimized by:

Maintaining good posture: Maintaining good posture can help prevent scapular winging by keeping the shoulder blades in the correct position and reducing strain on the muscles that support the scapula.

Strengthening the shoulder and back muscles: Strengthening the muscles that support the shoulder and back can help improve scapular stability and prevent winging.

Avoiding overuse or repetitive motions: Overuse or repetitive motions of the shoulder and upper back can increase the risk of scapular winging. Taking breaks, modifying activities, or using proper technique can help prevent injury and reduce the risk of winging.

Addressing underlying medical conditions: Certain medical conditions, such as nerve injuries or muscular dystrophy, can increase the risk of scapular winging. Treating these conditions can help prevent or minimize winging.

Seeking prompt medical attention: If you experience shoulder pain, weakness, or other symptoms of scapular winging, seek prompt medical attention. Early diagnosis and management can help prevent complications and improve outcomes.

It's important to work with a healthcare provider or physical therapist to develop an individualized prevention plan based on your specific needs and risk factors.

What are the 2 types of scapular winging?

The two types of scapular winging are:

Medial scapular winging: In medial scapular winging, the inner border of the scapula (the part closest to the spine) lifts away from the ribcage. This is typically caused by damage to the long thoracic nerve, which innervates the serratus anterior muscle.

Lateral scapular winging: In lateral scapular winging, the outer border of the scapula (the part furthest from the spine) lifts away from the ribcage. This is typically caused by damage to the accessory nerve or the trapezius muscle.

How do you test for scapular winging?

Scapular winging can be tested using the following methods:

Wall push-up test: The patient is asked to stand with their hands on a wall and perform a push-up motion while the examiner observes the movement of the scapula. If the scapula lifts away from the ribcage during the movement, this may indicate scapular winging.

Scapular assist test: The patient is asked to hold a weight or resistance band with both hands and lift it overhead while the examiner observes the movement of the scapula. If the scapula lifts away from the ribcage during the movement, this may indicate scapular winging.

Scapular retraction test: The patient is asked to hold their arms out in front of them and retract their shoulder blades while the examiner observes the movement of the scapula. If the scapula lifts away from the ribcage during the movement, this may indicate scapular winging.

Manual muscle testing: The strength of the muscles that support the scapula, such as the serratus anterior and trapezius muscles, can be tested using manual muscle testing. Weakness or muscle atrophy may indicate scapular winging.

If scapular winging is suspected based on these tests, imaging studies such as X-rays, MRI, or electromyography (EMG) may be ordered to confirm the diagnosis and determine the underlying cause.

Can winged scapula be fixed by exercise?

In some cases, scapular winging can be improved or even corrected through exercise. The effectiveness of exercise in treating scapular winging depends on the underlying cause and severity of the condition.

For example, if scapular winging is caused by weakness or imbalances in the muscles that support the scapula, targeted exercises can help improve muscle strength and function. Strengthening exercises may include exercises for the serratus anterior, such as wall push-ups, shoulder protraction exercises, and scapular push-ups, as well as exercises for the trapezius and rhomboid muscles.

However, if scapular winging is caused by nerve damage or structural abnormalities, exercise alone may not be sufficient to correct the problem. In these cases, other interventions such as surgery or physical therapy may be necessary.

It's important to work with a healthcare provider or physical therapist to develop an individualized exercise program based on your specific needs and the underlying cause of your scapular winging. They can also monitor your progress and adjust your exercise program as needed to ensure that you are making progress and not causing further damage.

How long is recovery for winged scapula?

The recovery time for scapular winging depends on the underlying cause and severity of the condition, as well as the treatment approach taken.

If scapular winging is caused by a nerve injury, recovery time may be longer and may involve a combination of surgery, physical therapy, and medication. Recovery time may range from several weeks to several months or longer, depending on the severity of the nerve damage and the individual's response to treatment.

If scapular winging is caused by muscle weakness or imbalances, recovery time may be shorter and may involve targeted exercises to strengthen the muscles that support the scapula. The length of recovery time will depend on the severity of the muscle weakness and how well the individual responds to exercise therapy.

It's important to work closely with a healthcare provider or physical therapist to develop a treatment plan that is tailored to your individual needs and to monitor your progress throughout the recovery process. They can also provide guidance on how to prevent future episodes of scapular winging and how to safely return to your normal activities.

What is the fastest way to fix a winged scapula?

There is no single "fastest" way to fix a winged scapula as the treatment approach will depend on the underlying cause and severity of the condition. However, there are some steps that can be taken to address the issue as quickly and effectively as possible:

Consult with a healthcare provider: If you suspect that you have scapular winging, it's important to consult with a healthcare provider who can perform a thorough evaluation and determine the underlying cause of the condition. Based on the diagnosis, the provider can recommend an appropriate treatment plan.

Begin physical therapy: Physical therapy can be an effective way to treat scapular winging caused by muscle weakness or imbalances. A physical therapist can develop an individualized exercise program to target the affected muscles and help improve strength and function. Starting physical therapy as soon as possible can help speed up the recovery process.

Consider surgery: In some cases, scapular winging may be caused by nerve damage or structural abnormalities that require surgical intervention. If this is the case, your healthcare provider may recommend surgery as the fastest way to address the issue.

Address contributing factors: In addition to exercise and/or surgery, it's important to address any contributing factors that may be exacerbating the condition, such as poor posture or improper lifting techniques. This can help prevent future episodes of scapular winging and promote faster healing.

It's important to remember that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to treating scapular winging, and recovery time can vary widely depending on the individual and the underlying cause of the condition. Working closely with a healthcare provider and physical therapist can help ensure the best possible outcome.

What nerve damage causes winging scapula?

The nerve damage that most commonly causes winging scapula is damage to the long thoracic nerve. This nerve innervates the serratus anterior muscle, which helps to stabilize the scapula against the ribcage during shoulder movements. If the long thoracic nerve is damaged, the serratus anterior muscle may become weak or paralyzed, leading to scapular winging.

The long thoracic nerve can be damaged by a number of factors, including trauma or injury to the shoulder or neck, surgical procedures in the area, or repetitive overhead activities such as throwing or serving. In some cases, the cause of the nerve damage may be unknown.

It's important to note that scapular winging can also be caused by other factors such as muscle weakness or imbalances, structural abnormalities, or neurological disorders. Therefore, a thorough evaluation by a healthcare provider is necessary to determine the underlying cause of the condition and develop an appropriate treatment plan.

What doctor treats winged scapula?

Several healthcare providers may be involved in the diagnosis and treatment of winged scapula, depending on the underlying cause of the condition. Some healthcare providers who may be involved in the care of patients with winged scapula include:

Orthopedic surgeon: An orthopedic surgeon is a medical doctor who specializes in the diagnosis and treatment of musculoskeletal conditions, including those affecting the shoulder and scapula. They may be involved in the surgical management of winged scapula, especially if the condition is caused by nerve damage or structural abnormalities.

Neurologist: A neurologist is a medical doctor who specializes in the diagnosis and treatment of conditions affecting the nervous system, including nerve damage that can cause winged scapula.

Physical therapist: A physical therapist is a healthcare provider who specializes in the evaluation and treatment of musculoskeletal conditions using exercise therapy, manual therapy, and other interventions. They may develop an exercise program to help strengthen the muscles supporting the scapula and improve function.

Sports medicine physician: A sports medicine physician is a medical doctor who specializes in the diagnosis and treatment of sports-related injuries and conditions. They may be involved in the care of athletes or individuals who develop winged scapula as a result of repetitive overhead activities or other athletic endeavors.

Primary care physician: A primary care physician is a medical doctor who provides general medical care and may be involved in the initial evaluation and management of winged scapula.

It's important to work closely with a healthcare provider or team of providers to determine the underlying cause of winged scapula and develop an appropriate treatment plan.

Summary

Winged scapula is a condition where the shoulder blade sticks out from the back, which can cause pain, weakness, and limited mobility. It can be caused by various factors, including nerve damage, muscle weakness or imbalances, structural abnormalities, or neurological disorders. The long thoracic nerve is the most common nerve that causes winged scapula due to damage or injury. The diagnosis of winged scapula involves a physical exam, medical history, and imaging tests, and treatment may include physical therapy, exercises, medication, or surgery. Several healthcare providers may be involved in the diagnosis and treatment of winged scapula, including an orthopedic surgeon, neurologist, physical therapist, sports medicine physician, and primary care physician. Preventive measures for winged scapula include good posture, proper form during exercise or sports, and avoiding repetitive overhead activities.